Women put anything that was sharp into their uteruses. Obviously, they were injured, but the point was to cause a hemorrhage and finally get rid of it all. In the countryside, one would use spindles, knitting or crocheting needles, and even a horseradish root or stems. Burdock was the best—it had a long, hard stem used for healing wounds. Worked like a disinfectant and was sharp like a knife. Perfect. I can’t look at a woman knitting now. Those needles make me think about one thing.

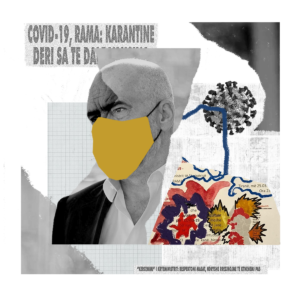

The Romanian television presenter announces that the General Secretary, Nicolae Ceaușescu, is deeply concerned with the attitude of Romanian women who don’t want to have children. In order to help them change this egocentric approach, Ceaușescu introduces Decree 770, according to which abortion will be penalized through imprisonment.

“This way,” announces the presenter, “we’re writing a new page in the history of our glorious fight against imperialist decadence.”

From 1 October 1966, contraception and abortion are allowed only for women who have fulfilled their patriotic duty and had at least four children. Or those who are older than forty and risk giving birth to a disabled child, whereas the nation needs “vitality, youth, and vigor.”

During the Ninth Rally of the Communist Party of Romania, Ceaușescu stresses that drastic measures are necessary and unavoidable. Party members agree—after the Secretary’s last words, they quickly stand up. The monotonous sound of clapping hands is heard around the hall.

The men and women are clapping.

The men are smiling, the women aren’t.

•

The next day, newspapers write with unfeigned acclaim about the farsighted policy of the General Secretary, who is making every effort to turn Romania into a global power. The Party coins a slogan: “Twenty-five million Romanians in 2000!” There are still six million missing, so female citizens better get to work.”

It will be easier for them because condoms disappear from the shops. One can still buy under-the-counter quinine globules, which cause a burning sensation that makes them closer to a corrosive agent than a contraceptive. Still, everyone is used to the fact that the actual solution to unwanted pregnancy is abortion.

Romanians are disorientated: the law was accepted overnight, and the majority of women have no idea about their physiology. There is no sex education, and hardly any mother can talk to her daughter about preventing pregnancy. Friends whisper among themselves: “pour some hot mămăligă inside,” “hop on one leg,” “run up and down the stairs.”

In 1967, twice as many babies are born in Romania than the year before. Children born in that record-breaking year will personally experience the failures of the state like no-one else: there will be no place for them in nurseries, kindergartens, and schools; there will be no work for them, and no flats.

When the revolution of 1989 began, the Decreței—the popular name for Romanians born in the years after the introduction of the new law—were entering adulthood. They came to realize that in collapsed communist Romania there was no future for them. They were disappointed and angry, and they wished death on the man who brought them into this world. Death to the Father of the Nation.

•

Meanwhile, in 1966 the Father of the Nation lectures Romanian women to have more babies, and Romanian women learn how to cope with this. They exchange tips and names. They prepare envelopes. They boil pots full of water. They spread plastic sheets. Standing in front of a rented flat, they say the password through the narrowly-opened door.

In communist Romania, the woman first had to be a worker, then a mother, and then a wife. In 1974, during the National Party Congress, one of the participants gave a passionate speech:

“Women have the full support of the Party. The Party creates conditions to treat them not like women, but as humans, equal to men.”

When the decree was introduced, Maria turned twenty-five and was, as she recalls, quite a babe. Today she’s almost seventy—thick glasses on a tiny nose, salt-and-pepper hair, petite body, bursting with energy. She’s lived her entire life in Bucharest, where she worked as a primary school director.

There is a Romanian saying: a woman is a milk cow and a draft ox. There’s also another: a woman is a horse to sit on, to tame, and to tie to a post. Such things stuck in people’s heads for centuries, since Turkish rule. Men took sex for granted. The notion of rape didn’t even exist, because what was that supposed to be? A woman was for sex, and that’s all. In the 1960s, I visited Poland and was supposed to meet my Polish friends in front of my hotel. I was waiting and waiting and nobody arrived. I met them the next day and asked why they didn’t come, and they replied: “But we did! We were waiting in the restaurant, by the door!” What?! In Romania, a woman couldn’t go to a restaurant alone. Alone?!

The situation was worst for women with children born out of wedlock.

“It was as if they had written ‘prostitute’ on their foreheads,” recalls Maria. “Sometimes, one managed to convince the guy to marry a pregnant woman, even for a few months, just to avoid the shame. In small towns, women who got pregnant ran away or waited until the birth, then left the child in the hospital and disappeared. There were many orphans in Romania, many ill children born after failed abortions. Only after Ceaușescu died was it revealed: these children lived in orphanages, in worse conditions than dogs—naked, sick, hungry. I was in a convenient situation because I had family abroad who could send me contraceptives. But it was a rare luxury. When I was invited somewhere, I brought cotton wool and condoms as a gift; the whole family would celebrate.”

Oana is a chubby sixty-year-old with mahogany hair. She talks fast and laughs a lot, even at things hardly anyone would find funny. She worked as an engineer and is now retired.

“Everyone knows these stories. Someone informed, someone got jailed. A woman who had an abortion went to prison for six months, the doctor—for two years and with a fine. Hospitals had special commissions that investigated the curettage of a patient with a hemorrhage: whether anyone had helped her miscarry. Women put anything that was sharp into their uteruses. Obviously, they were injured, but the point was to cause a hemorrhage and finally get rid of it all. In the countryside, one would use spindles, knitting or crocheting needles, and even a horseradish root or plant stems, like St. John’s wort or lovage. Burdock was the best—it had a long, hard stem was used for healing wounds. It was sharp like a knife and worked like a disinfectant. Perfect. I can’t look at a woman knitting now. Those needles make me think about one thing. Maybe it’s an obsession, I don’t know. I’m almost sixty-one; perhaps I was supposed to forget a long time ago? Recently I went with my husband on a trip outside the city. He likes fishing, and I sat on the blanket, looked at plants, at wormwood, nettle, thistle, and I thought: this would work, that wouldn’t.”

Women were dying from loss of blood or from infection.

“Helping the dying woman wasn’t allowed until she said who performed the abortion. You can imagine what a choice that was. For example, they would discover a midwife, and she had three patients that month. So they found out about those women. They had two, three kids, and nobody cared what happened when the mother went to jail. So many broken lives.”

Oana smiles quietly. She shakes her head as if she can’t believe her own words.

“Of course, I had abortions, like every other woman,” she continues. “Three times, each time my friends helped me find someone. It was entirely word-of-mouth: who does what and for how much. Dentist, mechanic, midwife. No matter if they were trained doctors, what counted was trust. I caused one miscarriage myself—I caused a hemorrhage and had to go to the hospital. I was very afraid, but I was lucky to meet a kind person there—he agreed to write ‘natural miscarriage’ on the documents. He didn’t even ask. Women tried to qualify for a cesarean because after two you were allowed to have a legal abortion. Still, it was difficult to bribe a doctor because hospitals had limits for cesareans: only every tenth birth could be resolved that way, so it was only used in life-threatening cases. I have a son. I don’t even think about those babies, and I tell you, every woman who had to go through that hell doesn’t even consider if it was moral or not. It wasn’t a case of morality but of dignity. We did what we could to live normal lives in those abnormal times.”

“Nobody ever wondered ‘do I have the right or not,” Maria shrugs. “People didn’t wonder whether they were enslaved or not. They were thinking about getting milk for the child or if there was anything in the shops. Please tell me, if the temperature in my flat was six degrees, would I think about rebelling against Ceaușescu, or about heating the bathroom so my daughter doesn’t get cystitis?”

The decree was in force for twenty-three years, but nobody protested or revolted.

Magazines for women from that era, like Femeia, claimed the abortion ban was lawful because mass-scale pregnancy termination would be a threat to social safety. They published statistics: sixty years ago, an average family had four children—now, only two.

The socialist economy needed new hands to work because they carry the weight of the system. In communist propaganda, “reproduction of the workforce” was described as “a special honor and a patriotic duty.” The production of new citizens was supposed to lead to the “prosperity of society and the victory of socialism in Romania.”

“One may wonder if the obedience of the Romanians was simply cowardice,” adds Maria. “But everyone remembered the rule of Gheorghiu-Dej in the 1950s when people disappeared overnight. They died in labor camps, out of hunger and exhaustion. Forty, sixty, one hundred thousand, nobody knows. Everyone lived with the awareness that they could disappear anytime without a trace.”

Nicolae Ceaușescu knew how to break those who resisted—with fear, and by pitting one against another so that society was self-regulating. The secret political police could see and hear everything. Bugs were installed on a mass scale, and where there were no bugs yet, they sent people. Colleagues at the factory would inform on each other. A nurse could report on the doctor—what he’s doing after hours, and for how much.

“My mother always told me to keep my mouth shut,” recalls Oana. “‘Nobody cares about your concerns,’ she repeated. ‘If they care, then they’ll want to use it against you.’ “

“Everyone was afraid of bugs and informers, everyone.” Maria shakes her head. “At work, when they began to say that it’s cold at home, that there’s no milk or meat, that we waited in a queue the whole night to get a box of eggs, I ran to the toilet and locked the door. What if someone informs that it’s me who complained? I’d just lost my husband, and I was worried that if I was jailed my daughter would be left alone. Someone even told me once: better keep in line, you only have one daughter—she’s a nice girl, it would be a pity if she had to go to an orphanage.”

•

Stefan, born in 1978, was his parents’ second child:

“Nobody talked about the decree at home. At school, children were talking about condoms, that this was something you put on your penis and it stopped you having more babies. And because you can’t buy them here, you have over forty kids in one class. Six Stefans, seven Cristinas, five Alexanders. Children asked each other: ‘Were you wanted?’ or called each other a flusher. I’ve never wondered about it because my parents were always good to me, they cared about me—I had no reason to think about it. But at some point, when I was a teenager, and a difficult one, I had an argument with my father. My mum commented: ‘Mind what you say because if it wasn’t for your father, you wouldn’t have been born.’ I immediately understood what she meant.

“A few weeks later, when she was making soup, I asked her if she had had one. She shrugged and said: ‘One here on the kitchen table, and the other one on the sofa in the living room.’ She kept making soup at the stove as if nothing had happened. I left the kitchen and cried. I’ve never asked her since about the decree or the abortions.”

According to various data, it is estimated that during the twenty-three years that the decree was valid, around nine-and-a-half-thousand to ten thousand women died in Romania due to complications after failed abortions. These are official statistics, but many researchers believe that actual numbers were higher.

Women usually had their first and second children and then made a decision about abortion when they knew that they couldn’t afford to have another one. This is why women who died due to post-abortion complications left orphaned children and helpless husbands.

Dan, born in 1974, a first child, recalls: “My good friend from primary school was brought up without his mother, and never mentioned her. Only when we were in our twenties—we’d known each other since childhood—and we got drunk together did he tell me that his mother died of a hemorrhage in a hospital because she didn’t want to say who performed her abortion. His father sat by the bed and begged her to tell because she was dying and he wasn’t able to care for the child on his own. But she wouldn’t change her mind. She said that she didn’t want to live in a country like that. My friend cried when he told me this.”

•

In Florin Iepan’s 2005 documentary Children of the Decree, the treatment of the “traitors of the nation” is shown. Those who died as the result of a failed abortion were condemned at universities and in their workplaces. Extreme situations occurred: in 1985, after the death of a young textile factory worker in Bucharest, the authorities demanded that the funeral procession stop under the factory window so that all the workers would be reminded of the possible consequences of an illegal procedure. The woman’s three children, who cried and shouted “Mum!,” witnessed it all.

“People don’t want to think about it,” says Oana. “It’s a tragedy of an entire society, which everyone would like to forget about. Everyone was hurt by it. Aside from Ceaușescu and his closest circle, there was no family that was unaffected.”

The breakthrough only came with Cristian Mungiu’s 2007 film 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days—a story about a pregnant student and her friend who go through all the circles of hell in communist Romania trying to organize an illegal abortion. The “emergency man” responsible for terminating advanced pregnancies takes advantage of the girls’ fear and rapes them. The amateur medic was played by Vlad Ivanov, who became one of Romania’s most popular actors on the wave of the film’s international success.

“Cristian cared about showing this film to as many people as possible, so he organized a ‘traveling cinema’ and screened it in villages and small towns,” says Ivanov.

But the evil experienced by the women was given Ivanov’s face.

“When we worked on my role, I was thinking that I was playing the devil, he adds. “Then it turned out that women didn’t perceive me as an actor, but as a character from the film, the man who performed the abortions. Often they cried when they saw me. I made them recall their fear and despair. I remember a situation in Tel Aviv. During the screening, Cristian and I were sitting in the cinema café. Suddenly, a woman stormed out of the cinema. She saw me, froze and began to cry. It turned out that she was a Jewish woman who lived in Ceaușescu’s Romania, and she’d been through that hell many times. She sat with us and shared her story. We knew such stories, they all were similar, but we had tears in our eyes.”

•

Gabriela is fifty-five years old. She’s an engineer, but for women who needed her help, it was the fact that her uncle was a doctor that mattered. Gabriela was a facilitator.

“Rule number one: we never performed an abortion at my uncle’s house, because it was obvious that he was under surveillance. We rented rooms, or the women found safe places on their own. We tried to bring anesthetics, but it wasn’t always possible. The women were brave. Determined. They screamed because it was an enormous pain. But they knew they had to hold on. Sometimes I can still hear their screams. Nothing else, because I don’t remember those women.”

“I had abortion twice, but four times I used my own method: when I noticed that my period was delayed, even by a few days, I immediately drank a few glasses of wine and ran to the bathroom to pour hot water all over myself. It hurts so much that you can’t even breathe, and you can’t stand it when you’re sober. But it always worked.”

“Some women had more than ten abortions—it became a routine: plastic sheet, hot water, curettage, back home. Please realize that I don’t know any women who had more than two kids. Maybe it was more difficult in the countryside, but in the city women always found a way to trick the authorities.”

“It’s no surprise that they chased everyone, everywhere. Women in factories had to undergo regular gynecological control—they said that it was uterine cancer prevention, but they were looking for fetuses. You went to a doctor with a toothache, and you ended up in the gynecological seat anyway: they had to ‘make sure you’re not pregnant because the medication can hurt your baby.’

“Uncle was eventually caught because he once took abortion tools out of the hospital and someone found out. He was sentenced to five years, as an example. And you know what? He was performing abortions in prison all the time because the guards were bringing their wives, daughters, and friends. Can you imagine? A man is jailed for illegal abortions, and the guard brings him hot water to disinfect the tools.”

In early 1988, Ceaușescu announces that the twenty-three millionth citizen has been born.

“We’re free people, lords of our fates,” the dictator lectures his nation. “We have a great homeland with a highly developed and constantly modernizing economy.”

The message to the nation occupies almost the entire broadcasting time for that day—due to the intensive economic crisis, the TV signal is transmitted for only two hours, from eight to ten p.m. Aside from that, a black screen.

In the 1980s, Ceaușescu decided that the energy of the nation would be used to pay national debts so that Romania could become fully independent. Groceries and natural resources were exported, with small amounts left for the domestic market. Special committees visited homes in order to check that nobody was using more than one light bulb, and no more powerful than forty watts. In winter, the temperature in the flats hardly ever reached ten degrees. Officially, it couldn’t be higher than twelve, but twelve was actually hot. Even hospitals weren’t heated, aside from the infant ward. If the mortality rate for newborns was higher than stipulated by law, doctors lost twenty percent of their salaries.

In 1989, hardly anyone believed that Ceaușescu would be gone, even though communism was collapsing throughout the Eastern Bloc. In Romania, even the most sensitive ear couldn’t hear the cracks in the system. The revolution only exploded in December when the people took to the streets.

“Ah, revolution,” Maria flicks her hand. “Please don’t call it this. Who the hell knows what it was? Not a coup, not an uprising. We know that the Russians and Americans had something to do with it. So much for the revolution.”

When Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu were sat in the stand during their swift trial, Elena kept on repeating: “Children, why do you do this to me? I am your mother!”

The death sentence was announced after a two-hour trial and performed immediately.

Dan was in Bucharest, in the crowd of protesters, when it was announced that Ceaușescu was dead.

“I jumped with joy,” he recalls. “I could have killed him with my bare hands, even though I’m ashamed of it. But Ceaușescu’s execution… it was something religious, a rite. Everything happened during Christmas, and after he was killed, snow fell everywhere in Romania. We killed him—people of the generation he created. The children who filled the streets, me included, were his children, children of the decree.”

“Ceaușescu’s death reminds me of the death of a scientist who performs a mad experiment and gets killed for its results,” says Olivia Nițiş, a feminist curator and art critic. “Romanian society is a society of silence: there is no tradition of rebellion against the authorities. So it’s not surprising that Ceaușescu did everything he planned: nobody even thought that they could resist.”

Totalitarianism entered people’s homes, looked into their kitchens and bedrooms. All human life was a matter for the state.

“Romanians still don’t want to discuss their past, and women don’t return to their experiences,” adds Nițiş. “There’s no reworking of the trauma or group therapy. Nobody wants to listen to women who went through the hell of the decree, and they don’t want to talk either.”

•

After Ceaușescu’s death, canceling the ban on abortion was the first change in the law. Today, pregnancy termination is once again treated as a method of contraception. It costs the equivalent of one or two hundred zloty, and it can be performed in any hospital.

In 2008, for every 220,000 births in Romania, there were 127,000 abortions.

Contrary to the hopes of the Father of the Nation, the twenty-five millionth Romanian wasn’t born by 2000. By then, the country had twenty-one-and-a-half-million citizens. The data from the last census surprised everybody: twenty-three years after Ceaușescu’s death, there are only nineteen million Romanians, which means that the population decreased by 12 percent within a decade.

The main reasons: emigration and low birth rate.

There are still six million citizens missing from the dream of twenty-five million.

(excerpted from Margo Rejmer, Bucharest: Dust and Blood trans. by Olga Drenda, 2013)