Xheni, Irena and Amaris all decided to turn their activism into a profession, only to find themselves caught between self-fulfilment and an uncertain future. Three activists report on the working conditions in the Albanian women’s movement.

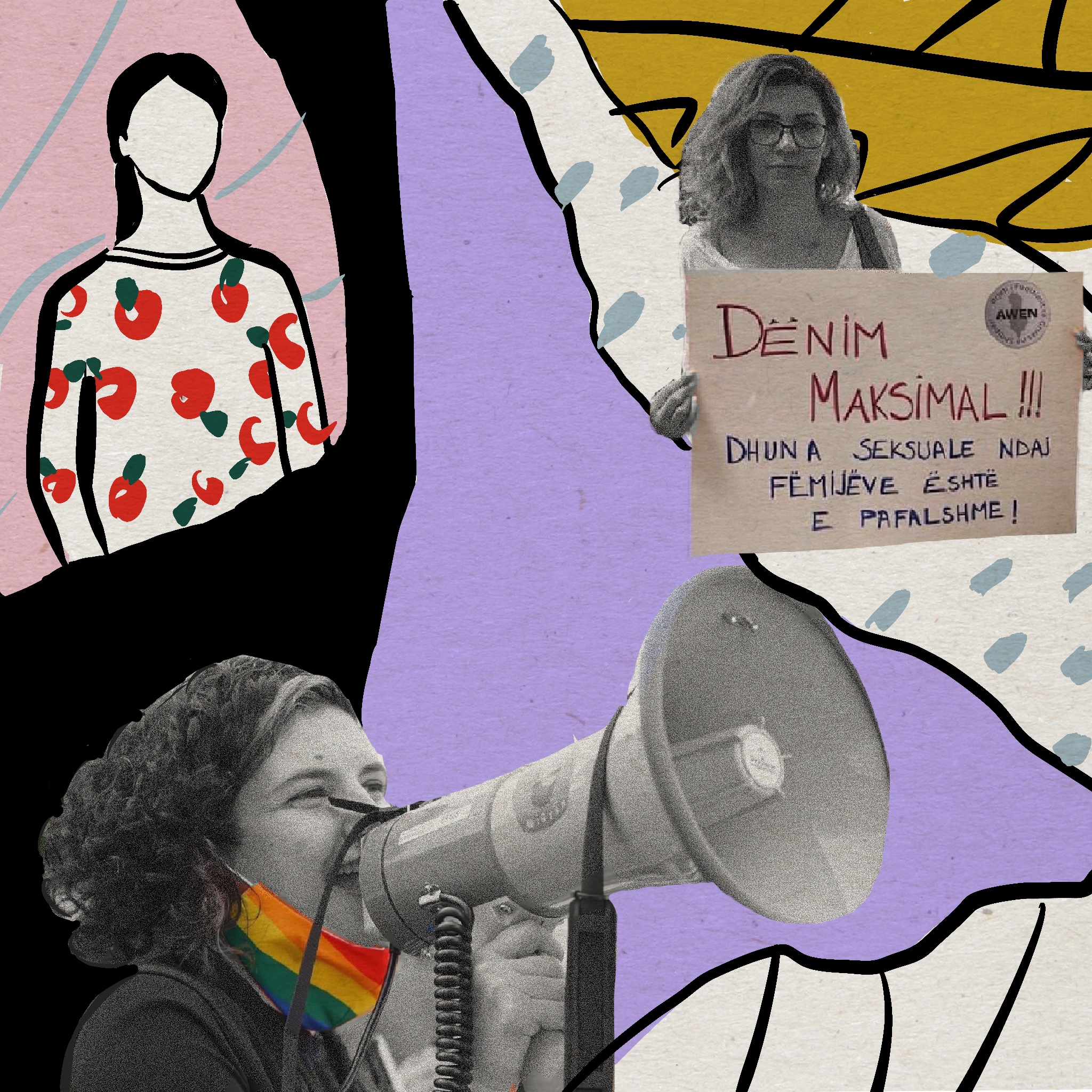

“We are lesbians, we are proud, we are radical feminists” – Xheni Karaj, 35, shouted into the megaphone.

It was International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia (IDAHOT), and a group of citizens had gathered in front of the University of Tirana, holding colourful balloons. They included many of the protagonists of Albania’s contemporary woman’s movement.

The new wave of feminists consists mainly of young women, some of whom have returned after studying abroad. Others have meanwhile gained experience within the student movement that mobilised thousands of people by the end of 2018.

Although working conditions in movement organizations are characterized by long workdays, lack of resources and recognition, some have turned their activism into a profession.

XHENI KARAJ: IT IS A MISSION

Xheni fights against homophobia full-time. She has been leading an LGBTQ+ organization for 12 years. Before she publicly outed herself on a TV show, she led a double life. By day she worked for the government, by night she was out as an activist pasting posters on walls. Neither her family nor her employer knew about her homosexuality, until the point came that her two lives could no longer coexist. So, she quit her job and devoted herself fully to the cause.

Xheni’s story is one of personal emancipation: „I started it for my own freedom, for myself, my well-being.” As a teenager, she suffered from depression. But then she found like-minded people with whom she could talk and gained confidence. “When you have found your peace, you ask yourself whether you should stop or continue for others.“ She opted for the latter and founded the NGO Aleanca LGBT, that has been growing ever since. Meanwhile, Aleanca provides various social services to the community and advocates equal rights.

As the leading director, Xheni has to translate activism into wage labour. This is a difficult balancing act because she considers the activities “not as just a job, but a life mission” and worries that “money could kill the spirit of activism”.

She is responsible for six employees, and receives no support from the government. Salaries are paid mainly through international donors, who also fund the organisation’s facilities. While this international support has enabled the institutionalisation of different structures within the organisation, and has increased its outreach, the project-based funding has created uncertainty at the same time.

“You live in constant fear of what might happen next.” The unpredictability affects her personal life. Although she would like to, she cannot afford to have children due to financial insecurity.

IRENA BEQJA SHTRAZA: IT COMES FROM THE HEART

The challenge of finding the ‘golden ratio’ between having a family and working in civil society is the reason that Irena Beqja Shtraza, 41, is leaving her current position at a well-known NGO in Tirana. „In many cases, working for an NGO is not enough to survive with children. You have to take on extra jobs and work weekends or nights.” She has been working in the civil society sector since she returned from Italy in 2007 and will now work for an international organisation, that is also focused on woman’s rights.

Irena describes herself as an “activist by soul” and her activism as a logical consequence of the patriarchal environment: “I am sensitive to injustice and at some point, became aware of what I have been through as a woman.” She has integrated feminism into her life and personality, which is why her activism won’t end with the new job: “it becomes about raising your kids and changing your brothers’ attitude”.

In order to improve the working situation of the actors, she would like to see greater and steady financial support from the government in the structures created by NGOs. This could also increase the influence of the movement, which is fragmented due to competition for funds.

AMARIS ANDREA: IT IS A CHOICE

Amaris sees this topic in a critical light: „We should rather put pressure on governments to take progressive substantive measures.“ Ultimately, she said, the existence of NGOs results from the government’s failure to perform certain tasks. At present, certain issues could not even be addressed without global solidarity.

She is one of Organizata Politike’s activists and employed by the associated Institute for Critique and Social Emancipation (IKESH) . Amaris supports the organisation of labour unions in textile and shoe factories, where mainly women work. She knows the situation of the workers, as her mother is also employed in one of the factories. Economically, Albania relies on competition through low wages, which is why many workers find themselves in precarious conditions. The monthly minimum wage is 210 euros and labour laws are often ignored. Lacking time and resources, the workers have hardly any chance to organise themselves.

BECAUSE THEY CARE

All three activists are committed to social change and seek to empower women. Their journey shows that participation in social movements is inextricably linked to other areas of life. The reason to join the women’s movement lies in their biography. Everyday experiences, such as family and work commitments, determine whether or how they continue to participate. Currently, the devaluation of care work by the neoliberal paradigm limits the female activists’ engagement. This is because they carry the double burden of unpaid care work at home while being underpaid for their professional work. It’s the neoliberal system that makes the activists careers precarious. Their economic necessities reveal the connection between classes and gender inequality and raise the question whether gender equality can be reached without socioeconomic equality. As the future progress of the movement is conditioned by the socioeconomic status and working conditions of the activists, a stable funding of core expenses, such as rent and salaries, is essential. Looking into the future, unpaid care work will also need to be addressed, reassessed and reorganised.